A childhood running wild in the forest merges with formative years shooting circus performers in Swedish photographer Bertil Nilsson’s latest work, soulful and surreal studies of impossibly adept physiques in rawest nature

Swedish photographer and filmmaker Bertil Nilsson produces work with an easy maturity that reflects his devoted, unassuming charecter and typically Swedish aversion to self-promotion. Exploring the sculptural beauty of the human form, his work has a distinctive style and thematic concern – acrobatic performers, usually nude, performing stunning contortions that, combined with Nilsson’s keen eye for framing and perspective, often look impossible. His imagery has a powerful stillness, each shot filled with a deep emotion that’s compellingly apparent to the viewer, yet hard to articulate.

It’s plain to see the powerful and enduring impression that his childhood in the Swedish countryside, and early experience photographing London’s young circus performers, have had on him. More surprising is his playful and enquiring attitude to his work. While his photographs seem masterful and controlled, it’s refreshing to meet an artist so comfortable admitting to the experimental nature of his process, and the lucky accidents that helped create iconic compositions.

‘I don’t really plan for these specific shots. Take one particular image, of the red body on the shore. I didn’t have the full idea to paint someone red, put them on the beach and have the colour wash away, it came from the process. I wanted to go into the sea, so we went, then we saw how the powder, which is just water-based paint, went really intensely red when the model swam, so we put it all over! I give some ideas and direction to it, but I think it’s more natural if it just happens.’

This spontaneity and playfulness has never been more apparent than in Nilsson’s recent collaboration with the Barely Methodical Troupe, in short film Bromance. The three trained circus performers run, backflip and execute acrobatics around London streets and in a kitchen. The film is infused with an intense affection and sensuality that, despite the hyperstylisation of the action onscreen, express a deeper relationship between the three men that transcends the ‘Are they? Aren’t they?’ questions hanging in the air.

‘It was my take on their show, but very condensed,’ says Nilsson. ‘They started training together when they were at school, and have done really well in a very short space of time. Their style mixes modern circus with classic elements. There are other people doing similar stuff, but Barely Methodical mixes technique with who they are. There’s no “mask” when they’re on stage, which is a very contemporary idea. They play together, their personalities come through – and they have the looks, of course. Some people can be technically great, but might not be able to translate their skills into a relevant show.

‘I’ve worked with them a lot, we’re friends, so it was natural for us to do this together. My idea was to show the narrative in a setting that merged a fantasy space with the real world, so we used my street in east London and a warehouse. But the film is all about them and their relationships.’

It was filmmaking that first drew Nilsson to London – he arrived in 2004 with dreams of working in the movie industry. ‘There aren’t really that many opportunities in Sweden unless you studied film at school or know the right people. The guy I was seeing had just moved from Stockholm, so it felt like several things were encouraging me to come here. I had been introduced to the circus world in Stockholm and, through my Swedish friends ended up living with some performers involved with London’s Circus Space, now the National Centre for Circus Arts. I had a camera and started taking pictures, exploring and learning.’

‘At the time, if you wanted to make cinema you had to shoot on film and needed very high-quality equipment to make anything of a decent standard, so equipment costs were a real barrier. In contrast photography was so much more accessible and direct. It’s a quick loop from having an idea to executing it and seeing the results. I was learning and progressing quicker, so I started to take it more and more seriously.’

Largely self-taught, Nilsson learned diligently by experimenting alone and working as a photographer’s assistant until his first book, Undisclosed: Images of the Contemporary Circus Artist won him serious recognition. ‘Very early on I decided I wanted to do a long-term project with the circus. I started it in 2006 and it came out in 2011. It took time to do, and while my goal remained the same, I found my sensibilities and aesthetic changed a lot in that time. I learned through working, and just pig-headedly decided I would stick with that project whatever.’

‘I was amazed by the circus artists, the level of commitment and how much hard work it is. It’s not totally glamorous, there are so many risks of injury, and even if you don’t get hurt, it’s often a short career that doesn’t pay a lot. But people still pursue it with such passion. I wanted to do a project that captured that, the soul of circus, I suppose.

‘I tend to find posed photography of movement uninteresting. You can feel the artifice somehow. I found that using a smaller digital camera I could move around and let my subjects move and express themselves better, in a more dynamic process. So when the final picture happened it was a magic moment of things all coming together. I think that’s why the photos have that feeling of genuine movement.’

Nilsson was drawn to the androgyny of acrobatics, which requires women to build muscle, while men cultivate flexibility and grace. In the physical language of circus he sees a dissolution of traditional gender attributes, and a crossing over of their expressions. A shared passion for their craft further heightens the convergence between the sexes, revealing itself in common ways of moving, and in some physical characteristics. For example, Nilsson points out, hands of male and female performers look the same, due to the discipline’s rigours.

‘The portraits show the performers in a uniquely intimate way, because there’s no mask involved, be that with make-up or clothes or a persona. And this is actually more exposed than a straightforward nude picture. When you’re spinning round with your legs apart in all sorts of different positions, you have to trust the person who is taking the pictures to represent you in a way that’s not always flattering, but with truth and dignity.’

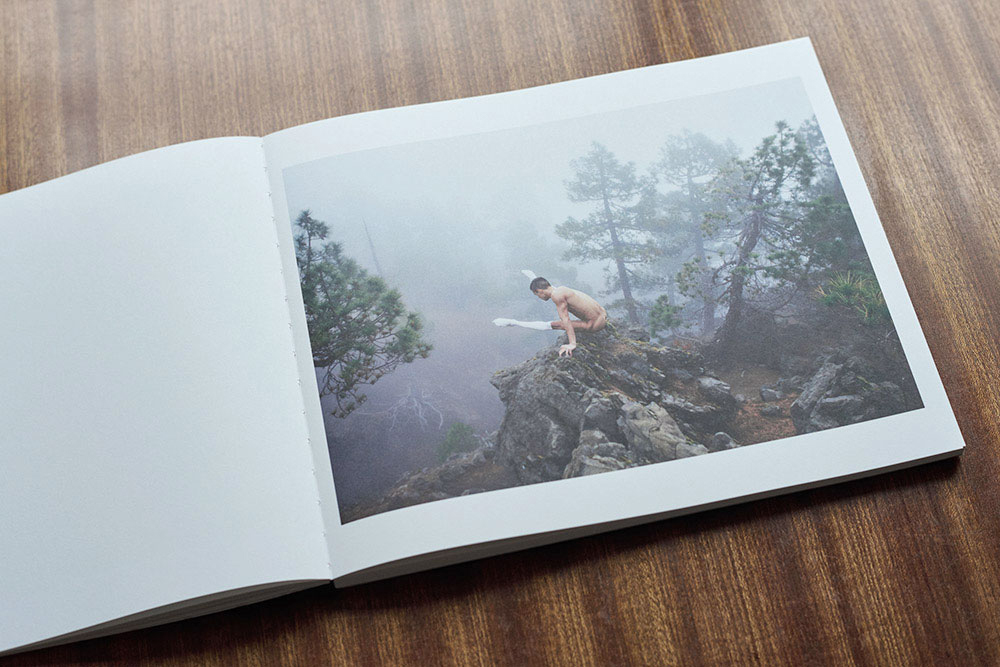

Nilsson’s newest work, Naturally, continues to explore these themes, working with dancers to showcase the beauty and capabilities of the human body. This series, however, is on a much grander scale, starkly juxtaposing man with nature, and playing with bright powders to create surreal images that flirt with bold symbolism.

‘I started experimenting with ideas around colours and powders. In the end these pictures became much more about me. I’m directing the situations more than I have before, and the colour interventions directly represent me, the artist’s hand in the work.

The body is the most natural thing we have, but what we choose to do with our bodies, particularly in acrobatics, is very unnatural. What I’m doing is adding naturally derived colours and bright objects to these moments, the artificial creations of man. Also, we tend to be culturally programmed to make specific clear associations with certain colours, like red or black, so a colour can add a whole new symbolic quality to a picture.

Nilsson describes the new work as ‘a personal journey’. As a child in the 1980s, the Swedish forests were his playground, day and night. Today he says parents don’t let kids run in the forest after dark, and he surrendered his own communion with nature when he moved to the city. For him, this new work became an excuse to set out on adventures, to fly to an island or walk into a forest, but this time with the mission of creating. ‘It’s been a different, interesting process. Yes, the compositions are controlled, but with the powder, you never know where it’s going to go, so you have to relax about that. And it’s amazing what people see in the pictures, just from simple things, a bit of flour, some red paint. In one picture a lot of people see an aborted foetus, but that’s not what I had in my mind of at all. There’s another image, of a man dancing on ground covered in white powder, his arms are thrown back and the action has almost created wings behind him, or it looks like his soul in a moment of exultation. I didn’t create these images for this symbolism, and it varies depending on the culture the viewer is from, I love seeing how people interpret things.’

Words by Kassandra Rodriguez

All images copyright Bertil Nilsson